📚 This is Part 2 of our 7-part series “Complete Money Education for Kids”:

- Part 1: Teaching Kids to Save ← Previous

- Part 2: Teaching Kids to Spend Wisely ← You are here

- Part 3: Teaching Kids to Earn ← Next

- Part 4: Teaching Kids About Budgeting

- Part 5: Teaching Kids About Debt

- Part 6: Teaching Kids About Investing

- Part 7: Teaching Kids About Giving

While teaching kids to save is essential (as we covered in Part 1), teaching them to spend wisely is equally important. After all, the purpose of money isn’t just to accumulate it—it’s to use it effectively to meet needs, create value, and bring joy.

Yet spending wisely is perhaps more challenging to teach than saving. Our consumer culture bombards children with advertising, creates artificial needs, and promotes instant gratification. Children see friends with the latest gadgets, influencers promoting products, and one-click purchasing that makes spending feel consequence-free.

The good news? Wise spending is a teachable skill. With the right approach, you can help your children develop the decision-making framework, critical thinking abilities, and self-control needed to spend money thoughtfully rather than impulsively.

This comprehensive guide will teach you how to educate your children about smart spending at every age, from distinguishing wants and needs to comparison shopping, understanding value, resisting marketing pressure, and making purchases that align with their values and goals.

Why Teaching Smart Spending Matters

Before diving into strategies, let’s understand why this matters so much:

Prevents Future Financial Struggles: Poor spending habits are the primary cause of financial stress in adults. People who struggle financially typically have income—they just spend unwisely. Teaching smart spending prevents decades of money problems.

Develops Critical Thinking: Learning to evaluate purchases builds broader analytical skills. Children learn to ask questions, compare alternatives, resist manipulation, and make evidence-based decisions—skills valuable far beyond shopping.

Builds Self-Control: Resisting impulse purchases strengthens the “delayed gratification muscle” that predicts success in multiple life domains including academics, relationships, and career.

Maximizes Life Satisfaction: Interestingly, research shows that people who spend thoughtfully report higher happiness than those who spend impulsively, even when spending the same amount. It’s not how much you spend, but how wisely.

Protects Against Marketing: Children today face sophisticated marketing from a very young age. Teaching them to recognize and resist these tactics is essential self-defense in the modern economy.

Complements Saving: No amount of saving helps if spending is out of control. The two skills work together—save consistently, spend wisely, and you’ll build wealth and life satisfaction.

The Psychology of Smart Spending

Understanding how spending decisions work in children’s (and adults’) brains helps you teach more effectively.

The Impulse vs. Deliberation Battle

Every spending decision involves two brain systems:

The Impulsive System (emotional, fast, automatic):

- Sees something attractive

- Imagines having it

- Feels desire intensely

- Wants it NOW

- Focuses on pleasure, ignores consequences

The Deliberative System (logical, slow, effortful):

- Evaluates actual need

- Considers alternatives

- Calculates true cost

- Thinks about tomorrow

- Makes rational comparisons

Young children have fully developed impulsive systems but immature deliberative systems. This is why a 4-year-old will have a meltdown over not getting a toy—their impulse system is screaming while their deliberative system barely exists yet.

Your teaching goal: Strengthen the deliberative system through practice and strategies, while acknowledging the impulse system’s power.

Marketing’s Impact on Children

Children are bombarded with sophisticated marketing:

- Volume: The average child sees 25,000-40,000 commercials per year

- Sophistication: Marketing uses psychological techniques to create desire and bypass rational thinking

- Peer pressure: Social media amplifies “everyone has this” feelings

- Influencer marketing: Kids see trusted personalities promoting products

- Artificial scarcity: “Limited time only!” creates panic buying

Children under 8 typically can’t distinguish advertising from content. Even teenagers are vulnerable to marketing tactics. Teaching media literacy and recognition of manipulation is crucial.

The Happiness-Spending Connection

Research reveals important insights about spending and happiness:

Experiences > Things: Spending on experiences (activities, trips, time with people) provides more lasting happiness than material purchases.

Anticipation Matters: The anticipation of a purchase provides happiness. Delayed purchases stretch out this anticipation phase.

Adaptation Occurs: We quickly adapt to new purchases (hedonic adaptation). The new toy thrills for days, then becomes ordinary.

Social Comparison Hurts: Spending to “keep up” with others reduces happiness because there’s always someone with more.

Aligned Spending Helps: Purchases that align with personal values provide more satisfaction than misaligned ones.

Use these insights when teaching: “That toy will be exciting for a few days, then you’ll get used to it. The soccer camp lasts a week but you’ll remember it for years.”

Age-Appropriate Spending Education

Let’s explore specific strategies for each developmental stage.

Ages 3-5: Basic Concepts and First Choices

The Wants vs. Needs Introduction

Even very young children can begin understanding the distinction:

Teaching approach:

- Use simple language: “Needs are things we must have to be healthy and safe. Wants are nice things we’d like but don’t need.”

- Make it concrete: “We need food. We want ice cream. We need clothes. We want that princess dress.”

- Play sorting games: Show pictures of items and sort into “need” and “want” piles

- Connect to their experience: “Remember when we needed medicine when you were sick? We wanted the toy, but we needed the medicine more.”

The Choice Framework

Give young children simple spending choices with clear trade-offs:

“You have $5. These stickers cost $3 and that small toy costs $5. Which would you like?”

This teaches:

- Money is limited

- Choices have consequences

- You can’t have everything

- Decisions must be made

The Waiting Strategy

Institute a simple waiting rule:

“When you see something you want, we put it on the ‘maybe’ list. If you still want it in three days, we can talk about buying it.”

This introduces delayed gratification and reduces impulse buying. Often, children forget about the item entirely.

Shopping Together

Bring young children shopping and narrate your decision-making:

“I need tomatoes. These cost $3 and those cost $4. They look about the same, so I’ll buy the $3 ones and save $1.”

“I want this fancy cheese, but it’s very expensive. I’ll buy the regular cheese because it’s a want, not a need.”

This modeling is powerful. They’re watching and learning your process.

Ages 6-9: Comparison and Value

The Comparison Shopping Game

Teach children to compare before buying:

Activity: When they want something, visit multiple stores (or check online) together:

- Store A: Toy is $25

- Store B: Same toy is $20

- Online: Same toy is $18 + $5 shipping = $23

Discuss: “Where should we buy it? Why? What did we learn?”

This teaches:

- Prices vary by location

- Research saves money

- Online isn’t always cheaper (shipping!)

- Thoughtful shopping pays off

The Quality vs. Price Concept

Introduce the idea that cheaper isn’t always better:

Example: Two backpacks:

- Cheap backpack: $15, will last one year

- Quality backpack: $40, will last five years

Do the math together: Five cheap backpacks = $75 vs. one quality backpack = $40

This teaches long-term thinking and “cost per use” calculation.

The Opportunity Cost Exercise

Before any purchase, discuss alternatives:

“This video game costs $50. What else could you do with $50?”

- Ten trips to the movies

- Fifty days of saving toward your bike

- Five books plus $25 saved

- Donate to animal shelter and still have $30

This doesn’t mean guilting them out of purchases—it means developing awareness that choosing one thing means not choosing others.

The “Cost in Time” Concept

If they earn allowance, convert prices to time:

“You earn $10 per week in allowance. That toy costs $30. That’s three weeks of allowance. Is it worth three weeks to you?”

This makes costs concrete and meaningful.

The Advertising Awareness Activity

Watch commercials together and discuss:

“What is this ad trying to make you feel?” “What did they show you? What didn’t they show?” “Do you think it’s really as amazing as they made it look?” “Who benefits if you buy this?”

This builds critical thinking and resistance to manipulation.

Ages 10-12: Strategic Thinking and Priorities

The Budget Game

Give them a hypothetical budget and list of wants:

“You have $100 for school clothes. Here’s what you want:

- Shoes: $60

- Jeans: $40

- Shirts: $30 each (you want three)

- Jacket: $80

You can’t afford everything. What do you choose and why?”

This teaches prioritization, trade-offs, and strategic decision-making.

The Review System

Before buying anything over a set amount (say $20), require them to:

- Wait 48 hours

- Research at least three options

- Write down pros and cons

- Explain why they want it

- Calculate opportunity cost

This creates a thoughtful decision-making framework.

The Used vs. New Exploration

Introduce the concept of buying used:

Activity: Look for a desired item:

- New price: $80

- Used (excellent condition): $40

- Used (good condition): $25

Discuss: “What matters more—new or functional? What could you do with the money saved?”

This teaches value-seeking and challenges “newness bias.”

The “Cost per Use” Calculator

Teach them to evaluate purchases by usage:

Example 1: $60 video game played for 100 hours = $0.60 per hour of entertainment Example 2: $60 toy played with twice = $30 per use

This framework helps them evaluate what’s actually worth buying.

The Marketing Deep Dive

Analyze marketing tactics more sophisticatedly:

- Scarcity: “Limited time!” “Only 3 left!”

- Social proof: “Everyone’s buying this!”

- Influencer endorsements

- Before/after manipulations

- Fake comparisons (comparing to overpriced alternatives)

Watch YouTube ads together and deconstruct the techniques. This builds immunity to manipulation.

The Values Alignment Exercise

Help them identify their values, then evaluate purchases against them:

“You say you care about animals and the environment. This brand tests on animals and uses lots of plastic packaging. Does buying this match your values?”

This teaches authentic decision-making rather than following trends.

Ages 13-18: Advanced Decision-Making and Financial Independence

The Total Cost of Ownership

Teach teenagers to calculate complete costs:

Example: Getting a pet

- Purchase: $50

- Food: $50/month = $600/year

- Vet visits: $200/year

- Supplies: $100/year

- Total year one: $950

- Ten-year ownership: $9,000+

Most purchase decisions focus only on acquisition cost. Understanding total cost changes decisions.

The Subscription Audit

Help them track and evaluate subscriptions:

- Streaming services: $15/month = $180/year

- Gaming subscription: $10/month = $120/year

- Music service: $12/month = $144/year

- Total: $444/year

Ask: “Do you use all of these enough to justify the cost? What if you eliminated one and put that $144 toward something else?”

The Lifestyle Inflation Discussion

Explain how spending tends to grow with income:

“When you get your first job, you’ll be tempted to upgrade everything—nicer phone, clothes, car, going out more. But if you spend every raise, you’ll never build wealth. The key is keeping lifestyle inflation below income growth.”

The Brand vs. Generic Comparison

Do structured comparisons:

- Brand name jeans: $80

- Similar quality generic: $30

- Difference: $50

“Is the brand name worth $50 to you? What’s really different—quality or just the label?”

This isn’t about never buying brands, but making conscious choices.

The Manipulation Resistance Training

Teach advanced marketing tactics:

- Anchoring (showing an expensive option first to make others seem reasonable)

- Decoy pricing (three options designed to push you toward the middle one)

- Loss aversion (“You’ll lose this deal!”)

- Artificial time pressure

- Fake discounts (price inflated then “discounted” to normal)

Once they see these tactics, they become harder to manipulate.

The Values-Based Budget

Help them create a budget that reflects their priorities:

If they value:

- Social connections: Budget more for activities with friends

- Fitness: Budget for gym, equipment, classes

- Creativity: Budget for art supplies, music, instruments

- Learning: Budget for books, courses, experiences

This teaches that spending should align with what truly matters to them, not what others value.

The Rent vs. Buy Analysis

For more expensive items:

“You want a $400 snowboard but only snowboard twice a year. Rental is $50/day. That’s $100/year. You’d need to use it four years to break even. Will you actually use it that much?”

This analytical approach prevents waste.

The Investment Opportunity Discussion

Show them the opportunity cost of spending vs. investing:

“You want to spend $1,000 on a new phone. If instead you invested that $1,000 at 8% annual returns, in 40 years it would be worth $21,700.”

Use our Compound Interest Calculator to show real numbers.

This doesn’t mean never spending—it means understanding the true cost.

Practical Strategies That Work Across Ages

Some strategies are effective across multiple age groups, with slight modifications.

The “Sleep on It” Rule

The concept: Never buy anything over a set amount immediately. Wait at least 24 hours (young kids) to 30 days (teens, adults) before purchasing.

Why it works: Impulse purchases are emotional. Time allows the emotion to fade and rational thinking to emerge. Often, the desire disappears entirely.

Implementation by age:

- Ages 3-5: Wait until tomorrow for wants over $5

- Ages 6-9: Wait three days for purchases over $10

- Ages 10-12: Wait one week for purchases over $25

- Ages 13+: Wait 30 days for purchases over $100

The “Three Questions” Framework

Before any purchase, ask:

- Do I need this or want this? (Honesty about the distinction)

- Will I still want this in a week/month? (Testing durability of desire)

- What am I giving up to buy this? (Opportunity cost)

If they can’t give good answers, they shouldn’t buy it yet.

The “Spending Journal”

Have children track every purchase for a month:

- What they bought

- How much it cost

- Why they bought it

- How they feel about it now

At month’s end, review:

- Which purchases were great?

- Which do they regret?

- What patterns do they notice?

- What would they change?

This builds self-awareness and learning from experience.

The “Cash Only” Method

Give younger children actual cash for purchases rather than using cards:

Why it works:

- Cash is tangible—they feel it leaving their hand

- When it’s gone, it’s gone (clear limit)

- They see the wallet getting emptier

- Research shows people spend 12-18% less with cash vs. cards

Once they’re older and need cards, this lesson will stick.

The “Want List” System

Create a running list of things they want:

- Write down every want

- Include the price

- Rank them by importance

- Revisit monthly

This teaches:

- Most “must have” items become “who cares” within weeks

- Priorities change

- Listing doesn’t mean buying

- Thoughtful selection over impulse

The “Value for Money” Framework

Teach them to evaluate purchases on multiple dimensions:

| Purchase | Cost | Quality | Durability | Joy | Value Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheap toy | $10 | Low | Days | Medium | 2/5 |

| Quality toy | $40 | High | Years | High | 5/5 |

| Experience | $30 | N/A | Memories | High | 5/5 |

This moves beyond just “what’s cheapest?” to “what provides best value?”

Teaching Through Real Purchases

Some of the best lessons come from allowing mistakes (within reason) and discussing outcomes.

The “Natural Consequences” Approach

Scenario: Your 9-year-old wants a toy you think is junk but they’ve saved for it.

Do this: Let them buy it (assuming it’s safe and not against family values)

What happens: It breaks in three days or they lose interest immediately

Your response: Don’t say “I told you so.” Instead: “You seemed disappointed it broke so quickly. What do you think about that purchase now? What might you do differently next time?”

Why it works: Experience is the best teacher. Better to learn about poor purchases with $20 than $2,000 later.

The “Comparison Shopping Mission”

Activity: They want something specific. Make research part of the process:

- Identify exactly what they want

- Check five different sources (stores, online)

- Compare prices, shipping, return policies

- Check reviews on quality

- Make the choice together

This teaches process, not just outcome. They’ll use this framework forever.

The “Buyer’s Remorse Discussion”

When they regret a purchase:

Don’t rescue them with a replacement or refund. Instead, have a thoughtful conversation:

“You seem unhappy with that purchase. What are you feeling?” “What made you want it in the first place?” “What’s different now than when you bought it?” “What would you do differently if you could do it again?” “What can you learn for next time?”

Frame it as valuable learning, not failure.

The “Great Purchase Celebration”

When they make a wise purchase:

Celebrate the smart decision-making:

“You researched for two weeks, compared prices, waited to make sure you really wanted it, and found a great deal. I’m really impressed with your thoughtful decision-making!”

Positive reinforcement strengthens the behavior.

Common Spending Traps and How to Avoid Them

Trap #1: Peer Pressure Spending

The problem: “Everyone has this phone/those shoes/that game!”

Solutions:

- Acknowledge the feeling: “I understand it’s hard when friends have things you don’t”

- Discuss whether “everyone” really means everyone or just a few visible people

- Talk about what makes them unique and valuable (not their possessions)

- Share your own experiences resisting peer pressure

- Discuss influencers’ motivation: “They’re paid to make you want things”

- If appropriate: “When you earn the money, you can choose to buy it”

Key message: Your value isn’t in your possessions. People who make you feel less-than because of what you don’t have aren’t good friends.

Trap #2: Sale and Discount Fever

The problem: “It’s 50% off! We should buy it!”

Solution: Teach the principle: “You don’t save money by spending money on things you don’t need.”

Exercise: Show how “sales” work:

- Item originally $100

- Marked up to $150 a month before sale

- “50% off sale” = $75

- You paid $75 for a $100 item and think you saved $75

Real savings only happens if you were going to buy it anyway at full price.

Trap #3: The Sunk Cost Fallacy

The problem: “I already spent $30 on this game, so I should buy the $20 expansion even though I don’t enjoy it.”

Solution: Explain: “The $30 is already spent. The question is: Is the expansion worth $20 right now? Would you rather have the expansion or $20 for something else?”

Past spending shouldn’t dictate future decisions.

Trap #4: Free Shipping Thresholds

The problem: “I need to spend $15 more to get free shipping!”

Solution: Calculate real cost:

- Item you want: $35 + $7 shipping = $42

- Item + something unnecessary: $50 + free shipping = $50

You spent $8 more to “save” $7 in shipping. That’s not saving.

Better: Pay the shipping or wait to buy until you actually need more items.

Trap #5: The Upgrade Trap

The problem: “My phone/computer/shoes still work, but there’s a newer version.”

Solution: Teach “functional replacement” vs. “upgrade desire”:

- Functional replacement: Current item is broken or no longer meets needs

- Upgrade desire: Current item works but newer one exists

Replace when needed, not when desired.

The upgrade frequency question: “How often do you really need the latest version? What if you upgraded every three years instead of every year?”

Teaching Money and Values

Spending decisions are ultimately value decisions. What we buy reflects what we care about.

Conscious Spending Alignment

Help children understand their own values:

Activity: List their top 5 values (maybe: family, creativity, adventure, helping others, learning)

Then review spending: “Does your spending reflect these values? If you value creativity but never buy art supplies, something’s misaligned.”

The Ethical Spending Conversation

As children mature, introduce ethical dimensions:

- Environmental impact: “This costs less but creates lots of plastic waste. This costs more but is sustainable. What matters more to you?”

- Labor practices: “This brand uses child labor. That one pays fair wages but costs more. What do you want to support?”

- Local vs. corporate: “Buy from the neighborhood shop or big corporation?”

These discussions build ethical reasoning and character.

The “Enough” Concept

In a consumer culture of “more is always better,” teach “enough”:

“You have 50 toys. Do you need another? When is it enough?”

“You have three pairs of shoes that work. Do you need a fourth pair?”

This isn’t about deprivation—it’s about contentment and knowing when you have sufficient.

The Experience vs. Possession Discussion

Share research showing experiences provide more happiness:

“Would you rather have this toy or a day at the amusement park with friends?”

“Would you prefer new clothes or a weekend camping trip?”

Help them notice: They remember and talk about experiences long after material purchases are forgotten.

Digital Age Spending Challenges

Modern children face unique spending challenges:

One-Click Purchasing

The problem: Buying is too easy online. No handing over cash, no friction, no feeling the cost.

Solutions:

- Disable one-click purchasing on family accounts

- Require password entry for purchases

- Use gift cards with set limits rather than linked credit cards

- Delay delivery when possible (choose slower shipping)

- Review orders together before finalizing

In-App and Game Purchases

The problem: “Free” games with constant purchase prompts. Virtual currencies that disguise real costs.

Solutions:

- Disable in-app purchases entirely for younger kids

- Give older kids a monthly game budget—once it’s gone, it’s gone

- Discuss how game developers manipulate: “They make you wait unless you pay. That’s designed to frustrate you into spending.”

- Show real costs: “$5 for 500 gems sounds small, but you’ll need 5,000 gems for that item, so that’s actually $50”

Influencer Marketing

The problem: Trusted personalities promoting products, often without clear disclosure.

Solutions:

- Teach recognition: “When they show a product and say how great it is, they’re usually paid to do that”

- Discuss motivation: “Why would they show you this? Who benefits?”

- Encourage skepticism: “Do you think it’s really that amazing or are they acting?”

- Follow ethical influencers who are transparent about sponsorships

Social Media Pressure

The problem: Constant exposure to others’ possessions and lifestyles.

Solutions:

- Discuss the “highlight reel” effect: People show their best, not their reality

- Limit social media exposure for younger children

- Talk about photo manipulation and curation

- Emphasize that possessions don’t create happiness or friendship

- Consider: “If no one saw this purchase, would you still want it?”

Tools and Resources for Teaching Smart Spending

Apps and Games

For Younger Kids (6-10):

- Needs vs. Wants - Simple game categorizing items

- Money Metropolis - World Bank game teaching financial decisions

- Bankaroo - Virtual bank for tracking saving and spending

For Older Kids and Teens:

- Goodbudget - Envelope budgeting system

- YNAB (You Need a Budget) - Full budgeting tool (ages 13+)

- Mint - Spending tracking (ages 16+)

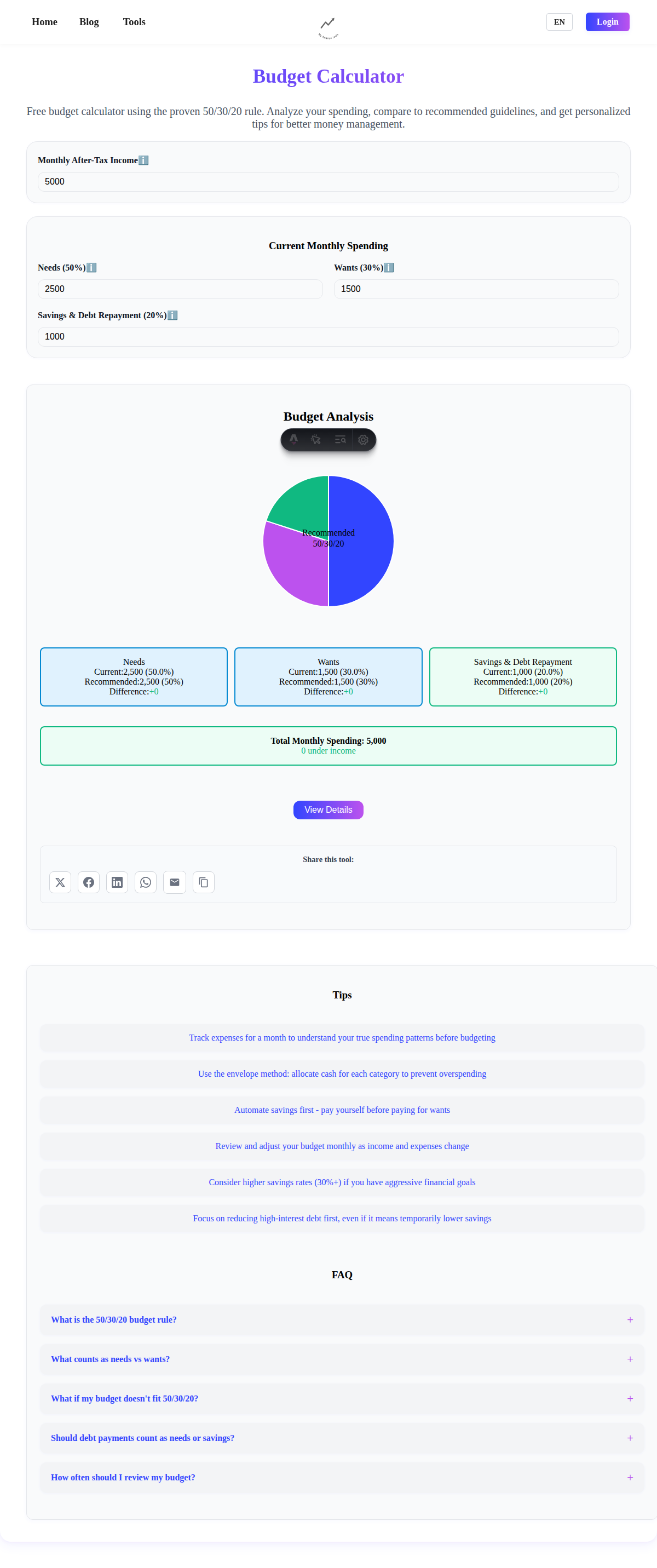

- Use our Budget Calculator to plan spending allocation

Books

Ages 5-8:

- “What to Do with a Dollar” by Wade W. Horton

- “Once Upon a Dime” by Nancy Kelly Allen

- “Lemonade in Winter” by Emily Jenkins

Ages 9-12:

- “The Kids’ Money Book” by Jamie Kyle McGillian

- “Smart Money Smart Kids” by Dave Ramsey and Rachel Cruze

- “Not Your Parents’ Money Book” by Jean Chatzky

Teens:

- “The Opposite of Spoiled” by Ron Lieber

- “I Will Teach You to Be Rich” by Ramit Sethi (upper teens)

- “Your Money or Your Life” by Vicki Robin (upper teens)

Real-World Practice

Grocery Shopping Exercise Give your child $20 and a shopping list. They must buy everything on the list within budget:

- They’ll compare brands

- Use coupons

- Calculate running totals

- Make trade-off decisions

The Birthday Party Budget Planning a birthday? Give them the total budget and let them allocate:

- Venue

- Food

- Decorations

- Activities

- Party favors

They’ll quickly learn everything costs more than expected and prioritization is essential.

The Vacation Planning Exercise Planning a family trip? Include older kids in the budget:

- Accommodation options at different price points

- Activities and their costs

- Food budget

- Trade-offs: “More expensive hotel means fewer activities”

Connecting to Other Money Skills

Smart spending doesn’t exist in isolation. It connects to every other financial skill in our series:

- Saving (Part 1): You can’t save without controlled spending. They’re two sides of the same coin.

- Earning (Part 3): Understanding what things cost shows how many work hours they represent.

- Budgeting (Part 4): Budgets allocate money to different spending categories thoughtfully.

- Debt (Part 5): Overspending leads to debt. Smart spending prevents it.

- Investing (Part 6): Money not spent unwisely can be invested for growth.

- Giving (Part 7): Ethical spending connects to using money for good in the world.

Taking Action Today

Ready to start teaching smart spending? Here’s where to begin:

For Young Children (3-5):

- Start the “wait until tomorrow” rule for wants

- Play the wants vs. needs sorting game

- Narrate your own spending decisions aloud

- Give them small choices between two items

For Elementary Age (6-9):

- Before their next purchase, comparison shop together at three places

- Institute the “three questions” framework

- Watch a commercial together and discuss the manipulation tactics

- Calculate “cost per use” for something they want

For Pre-Teens (10-12):

- Start a spending journal for one month

- Do a “total cost of ownership” calculation for a pet, phone, or hobby

- Give them a budget for school clothes and let them make all decisions

- Discuss the difference between needs and wants in your own spending

For Teenagers (13+):

- Review their subscriptions and calculate annual costs

- Use our Budget Calculator to create their first real budget

- Have the “investment opportunity cost” discussion

- Give them control over a major purchase (with guidance)

Conclusion

Teaching children to spend wisely is one of the most valuable gifts you can give them. In a world designed to separate people from their money as quickly as possible, thoughtful spending is both a financial skill and a form of self-defense.

Start early with simple concepts. Build gradually toward sophisticated analysis. Model thoughtful spending in your own life. Allow them to make mistakes on a small scale so they learn lessons before the stakes are high.

Remember that the goal isn’t creating misers who never spend. It’s raising adults who spend intentionally, in alignment with their values, and who use money as a tool for building the life they want rather than impulsively reacting to every desire and marketing message.

The children who learn to spend wisely don’t just save more money—they experience less stress, greater life satisfaction, and the confidence that comes from making conscious choices rather than being pushed around by impulses and manipulation.

Smart spending is freedom. Give your children that gift.

Continue Your Journey

Ready to teach your kids about earning money and developing a strong work ethic? Continue with Part 3: Teaching Kids to Earn to explore allowance strategies, age-appropriate money-earning opportunities, and building entrepreneurial thinking.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I teach my child to spend wisely without making them fear spending altogether?

Balance is key. Emphasize that spending thoughtfully on things that matter is good—it’s thoughtless or impulsive spending that causes problems. Use the 50/40/10 approach from Part 1: Some money is for spending freely, some for saving, some for giving. The spending portion is guilt-free—they’re learning to enjoy money while also learning to be thoughtful with it. Celebrate smart purchases as much as successful saving. The goal is wise spending, not no spending.

My child is constantly asking for things their friends have. How do I handle the peer pressure?

First, validate their feelings: “I understand it’s hard when friends have things you don’t.” Then discuss whether the desire is really theirs or just social pressure. Ask: “If you were the only person who knew you had this, would you still want it?” Teach them that their value doesn’t come from possessions. Consider compromises: “If you want this badly enough to save your own money for it, you can buy it.” Often, they lose interest when it’s their money. Most importantly, help them find identity and confidence in things beyond possessions.

Should I ever say “no” to purchases or always let them decide if they have the money?

Parents should absolutely maintain veto power. Just because they saved money doesn’t mean every purchase is appropriate. Reasonable boundaries include: safety concerns, items against family values, age-inappropriate content, things that would harm them or others, or purchases of dubious legality. You might say: “I respect that you saved for this, but I’m not comfortable with this purchase because [reason]. Let’s talk about alternatives.” The goal is teaching wisdom, not just choice-making.

What if my child always chooses the cheapest option, even when quality matters?

Some children overcorrect and become excessively frugal. If this happens, teach “value” vs. just “price.” Show cost-per-use calculations: “These $10 shoes will last three months. These $30 shoes last two years. Which is actually cheaper?” Sometimes, demonstrate the lesson: Let them buy the cheap version, watch it break quickly, and discuss the experience. Explain: “Being smart with money doesn’t mean always choosing the cheapest—it means choosing the best value.” Our Budget Calculator can help them see how to allocate money thoughtfully across different categories.

How do I handle gift money from relatives who expect my child to buy toys?

This is tricky because gift-givers sometimes have expectations. A balanced approach: Let your child spend some percentage (maybe 50%) on something fun now, while saving or investing the rest. This satisfies the gift-giver’s desire to see the child enjoy something, while also teaching good habits. You might photograph the purchase and send a thank-you showing what the child bought. Explain to your child: “Grandma wants you to enjoy this gift, so let’s buy something special with some of it. The rest we’ll save for your bigger goal.”

What about expensive items like phones or computers that kids need for school?

Distinguish between actual needs (for school/safety) and wants (latest model, premium features). Consider a shared cost approach: “You need a phone. We’ll cover a basic functional phone. If you want the premium model that costs $400 more, you can save and pay the difference.” This teaches both responsibility and reality—adults often make similar calculations: what do we need vs. what do we want, and what are we willing to pay extra for? For truly necessary items, parents should provide basic functionality without requiring kids to fund essentials.

How do I teach smart spending when I struggle with it myself?

This is incredibly common and honest. Consider: (1) Use this as an opportunity to improve together: “I’m working on being smarter with money too. Let’s help each other.” (2) Be transparent about your own mistakes: “I bought this impulsively and regret it. Here’s what I learned.” (3) Model the process even if you’re not perfect: “I want to buy this, but I’m going to wait a week to make sure I really want it.” Kids benefit from seeing adults work on improvement, not just from seeing perfection. Growing together is powerful. Consider reading our complete series together and implementing strategies as a family.

At what age should I let my child make spending decisions completely independently?

This should be gradual. Around ages 6-8, they can make independent decisions on small purchases (under $10) with guidance. Ages 9-12, they can handle more ($25-50) with light supervision. Ages 13-15, they can make most routine decisions independently while discussing major purchases with you. Ages 16-18, they should be making most decisions independently, coming to you mainly for advice on major purchases or when they want input. By 18, they should be fully independent decision-makers. The key is gradually extending independence while remaining available for guidance, and watching how they handle increasing responsibility.