📚 This is Part 4 of our 7-part series “Complete Money Education for Kids”:

- Part 1: Teaching Kids to Save

- Part 2: Teaching Kids to Spend Wisely

- Part 3: Teaching Kids to Earn ← Previous

- Part 4: Teaching Kids About Budgeting ← You are here

- Part 5: Teaching Kids About Debt ← Next

- Part 6: Teaching Kids About Investing

- Part 7: Teaching Kids About Giving

After teaching children to save (Part 1), spend wisely (Part 2), and earn money (Part 3), the next critical skill is bringing it all together through budgeting—the art and science of planning what to do with money before you spend it.

Budgeting is perhaps the most practical and immediately useful financial skill anyone can develop. Adults who budget report less financial stress, achieve goals faster, save more, and feel more in control of their lives. Yet most people never learned to budget as children, making it feel mysterious, restrictive, or overwhelming as adults.

The good news? Budgeting is remarkably simple to teach, especially when started young. Children naturally grasp the concept of planning and allocation when presented in age-appropriate ways. A child who learns to budget at age 8 will find it intuitive at age 28, while someone trying to learn budgeting for the first time at 30 faces a much steeper learning curve.

This comprehensive guide will teach you how to introduce budgeting concepts at every age, from simple jar systems for young children to sophisticated financial planning for teenagers, creating a foundation for lifelong financial management.

Why Teaching Budgeting Matters

Budgeting is the skill that makes all other money lessons functional.

Prevents Financial Chaos: Without a budget, money flows unpredictably—sometimes there’s enough, sometimes there isn’t, and you never know which. Budgeting creates order and predictability.

Enables Goal Achievement: Budgets transform wishes into plans. “I want to save for a bike” becomes “I’ll allocate $20 per month to bike savings for 6 months.”

Reduces Stress: Research consistently shows that people who budget report significantly lower financial stress, even at similar income levels. Knowing where your money is going creates peace of mind.

Teaches Trade-offs: Budgeting makes opportunity costs visible. Spending $50 on one thing means not spending it on another. This awareness drives better decisions.

Builds Planning Skills: Budgeting is fundamentally about planning—thinking ahead, anticipating needs, preparing for challenges. These skills transfer to academics, career, and life.

Prevents Overspending: A budget creates healthy constraints. When the entertainment category is spent, entertainment stops until next month. This prevents the accumulation of debt.

Maximizes Money: Paradoxically, people who budget often feel they have more money, even though income hasn’t changed. Why? Less waste, fewer impulse purchases, and better allocation to what truly matters.

The Psychology of Budgeting

Understanding how budgets work psychologically helps you teach them effectively.

Budgets as Freedom, Not Restriction

Many people view budgets as restrictive—a list of “can’ts.” This makes budgeting feel punitive.

Reframe budgets as permission slips: “You have $30 in your entertainment budget this month. That means you can spend up to $30 guilt-free on fun. No second-guessing, no regret. Enjoy it!”

This positive framing—budgets create freedom within boundaries—makes budgeting appealing rather than dreaded.

The Envelope Psychology

Physical cash in envelopes (or jars for kids) creates powerful psychological constraints that digital tracking doesn’t:

- You can see money depleting

- When it’s gone, it’s visibly gone

- Moving money between envelopes requires conscious action

- Physical handling creates emotional connection

This is why cash-based systems work so well for beginners, especially children.

Mental Accounting

Humans naturally do “mental accounting”—mentally categorizing money for different purposes. Budgeting simply makes this explicit and systematic.

Children already do this: “This is my birthday money so it’s special” (different mental category than allowance). Budgeting leverages this natural tendency.

The Pain of Payment

Research shows that paying with cash “hurts” more than cards because it’s tangible. This natural restraint is valuable for learning.

As children progress to digital money, they lose this feedback. Budgeting replaces the lost feedback mechanism with conscious categories and limits.

Age-Appropriate Budgeting Education

Let’s explore specific strategies for each developmental stage.

Ages 3-5: Introduction to Allocation

Very young children can grasp basic allocation concepts.

The Two-Jar System

Start with the simplest possible budget: two categories.

Implementation:

- Two clear jars labeled with pictures (since they can’t read yet)

- Jar 1: “Spend Now” (picture of toys)

- Jar 2: “Save” (picture of piggy bank)

- When they receive money, help them divide it: “Two coins in Spend, one coin in Save”

What they learn:

- Money gets divided for different purposes

- Not all money is for immediate spending

- Planning ahead matters

The Three-Jar System

Add a third category for a more complete introduction:

- Jar 1: “Spend” (40-50%)

- Jar 2: “Save” (40-50%)

- Jar 3: “Share” (10%)

Example: $5 allowance

- $2.50 in Spend (for things they want soon)

- $2.00 in Save (for bigger things later)

- $0.50 in Share (for giving to others)

Activity: Count money together weekly:

- “You have $7 in your Spend jar. What could you buy?”

- “You have $15 in your Save jar. You’re getting closer to that toy!”

- “You have $3 in your Share jar. Ready to give to the animal shelter?”

Visual Emphasis: At this age, seeing the money accumulate in different jars is more impactful than any tracking system.

Ages 6-9: First Real Budgets

Elementary-age children can handle more sophisticated categories and planning.

The Expanded Jar/Envelope System

Introduce 4-5 categories that match their life:

Category 1: Spending Money (30%)

- For small purchases they want now

- Candy, small toys, stickers, etc.

- They control this completely

Category 2: Savings Goal (30%)

- For their current big goal (toy, game, etc.)

- Specific and time-bound

- Track progress visually

Category 3: Long-term Savings (20%)

- For distant future (eventually something really big)

- Might go into a bank account

- Building wealth slowly

Category 4: Giving (10%)

- Charity, gifts for family/friends, helping others

- Teaches generosity

Category 5: Emergency/Backup (10%)

- For unexpected needs or opportunities

- Teaches preparedness

Example with $10 weekly allowance:

- Spending: $3 (spent freely)

- Savings Goal: $3 (currently saving for $60 scooter)

- Long-term: $2 (growing steadily)

- Giving: $1 (collecting for donation)

- Emergency: $1 (backup fund)

The Budget Planning Conversation

Before they receive their allowance, discuss allocation:

“You’re getting $10 this week. How will you divide it?”

Guide them to their budget categories, but let them participate in the decision.

The Tracking Chart

Create a simple visual chart:

Week 1:

Spending: ✓✓✓ ($3)

Savings Goal: ✓✓✓ ($3) - Total: $15 of $60

Long-term: ✓✓ ($2) - Total: $8

Giving: ✓ ($1) - Total: $4

Emergency: ✓ ($1) - Total: $5This shows money flow and accumulation.

The Budget Review

Weekly or bi-weekly, review together:

- What did you spend from your Spending jar?

- Are you happy with those choices?

- How much closer are you to your savings goal?

- Is anything left in your Spending jar? (If so, they could move it to savings)

- Any changes needed to the plan?

First Budget Adjustments

When they want something that doesn’t fit the budget, teach adjustment:

“You want that $8 toy but only have $3 in Spending. Your options:

- Wait until next week when you have $6

- Take some from Savings Goal (but your scooter will take longer)

- Earn extra money doing additional chores

- Decide you don’t want it enough

What do you think?”

This teaches real budget trade-offs.

Birthday/Gift Money

When they receive larger amounts, apply the same system:

“You got $50 for your birthday! Using your budget:

- Spending: $15 (buy something fun!)

- Savings Goal: $15 (wow, your scooter goal just got much closer!)

- Long-term: $10

- Giving: $5

- Emergency: $5”

Consistency across income sources reinforces the habit.

Ages 10-12: Sophisticated Planning

Pre-teens can handle more complex budgeting with increased categories and responsibility.

The Categories Expansion

Expand to 6-8 categories matching their expanding life:

- Day-to-Day Spending (20%): Small regular purchases

- Entertainment (15%): Movies, games, activities with friends

- Short-term Savings (20%): Current goal (1-3 months away)

- Medium-term Savings (15%): Bigger goal (3-6 months away)

- Long-term Savings (15%): Distant future (6+ months)

- Giving (10%): Charity and gifts

- Education/Books (5%): Learning materials, books

The Written Budget

Transition from physical jars to written tracking:

Monthly Budget Example (assuming $40/month income from allowance and extra chores):

| Category | Budgeted | Spent | Remaining |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day-to-Day | $8 | $5.50 | $2.50 |

| Entertainment | $6 | $6.00 | $0 |

| Short-term Savings | $8 | $0 | $8 |

| Medium-term Savings | $6 | $0 | $6 |

| Long-term Savings | $6 | $0 | $6 |

| Giving | $4 | $4.00 | $0 |

| Education | $2 | $0 | $2 |

| Total | $40 | $15.50 | $24.50 |

Update this weekly or after purchases.

The Budget Planning Process

Teach them to create their own budget:

Step 1: Calculate Total Income

- Allowance: $10/week = $40/month

- Extra chores: Average $10/month

- Total: $50/month

Step 2: List Financial Goals

- Short-term: New video game ($50) - want in 2 months

- Medium-term: Bike upgrade ($150) - want in 6 months

- Long-term: Laptop fund (helping with cost, saving $500 over 18 months)

Step 3: Determine Necessary Expenses

- School lunch supplementation: $10/month

- Phone game subscription: $5/month

- Total necessities: $15/month

Step 4: Allocate to Goals To reach goals on timeline:

- Short-term: $25/month for 2 months = $50

- Medium-term: $25/month for 6 months = $150

- Long-term: $28/month for 18 months = $504

But this is $78/month with only $50 income! Time for prioritization.

Step 5: Adjust and Prioritize

- Keep short-term goal: $25/month

- Extend bike to 8 months: $19/month

- Extend laptop to 24 months: $21/month

- This leaves… -$15/month. Still doesn’t work!

Step 6: Make Trade-offs

- Eliminate phone subscription: Saves $5/month

- Reduce short-term goal slightly: $20/month (will take 2.5 months, acceptable)

- Bring own lunch 2 days/week: Saves $5/month

- Now: $50 income - $20 (short-term) - $19 (medium-term) - $11 (long-term) = $0

Wait, there’s no fun money!

Step 7: Reality Check Need to either:

- Earn more money (take on additional chores/jobs)

- Adjust goals (extend timelines or reduce amounts)

- Accept less discretionary spending

Final Budget:

- Earn extra $15/month through additional work

- Income now $65/month

- $20 short-term savings

- $19 medium-term savings

- $11 long-term savings

- $10 fun/discretionary

- $5 giving

- Total: $65

What they learned: Creating a budget requires research, math, prioritization, and trade-offs—exactly what adults do.

Use Technology

Introduce budgeting apps:

- Greenlight (debit card with budgeting features)

- FamZoo (virtual family bank)

- Mint (simple tracking, for older pre-teens)

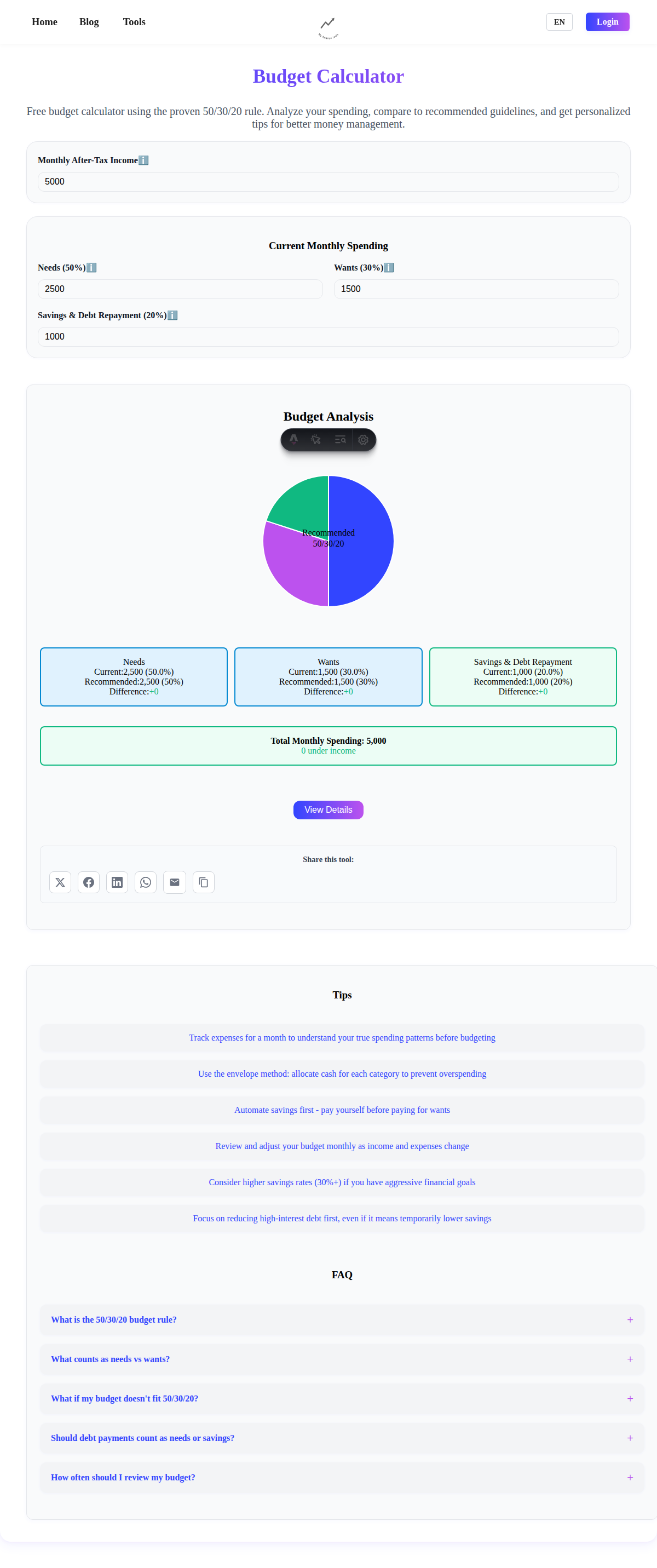

- Our Budget Calculator for planning

The Monthly Review

End of each month, conduct comprehensive review:

“Let’s look at your budget:

- You stayed under budget in Day-to-Day spending. Great discipline!

- You went over in Entertainment by $3. What happened?

- You hit all your savings goals. Excellent!

- Your short-term goal is 80% complete. One more month!

For next month:

- Move that extra $2.50 from Day-to-Day to short-term savings?

- Increase Entertainment budget by $3 since that’s more realistic?

- Any goals changing?”

This teaches analysis, adjustment, and continuous improvement.

The Irregular Income Challenge

If they have irregular income (sometimes earn extra, sometimes don’t):

Teach conservative budgeting:

- Budget based on minimum expected income

- When extra arrives, decide: accelerate goals, increase discretionary, or bank it for low-income months

This mirrors adult freelance/commission income management.

Ages 13-18: Real-World Financial Management

Teenagers can manage sophisticated budgets approaching adult complexity.

The Complete Budget

Teenagers should create comprehensive budgets covering all aspects of life:

Income Sources:

- Part-time job

- Allowance (if still receiving)

- Gift money (average)

- Side hustles

- Total expected monthly income

Example: High school junior with part-time job

Income:

- Job: $12/hour × 15 hours/week × 4 weeks = $720/month

- After taxes (roughly 15%): $612/month

- Birthday/gifts averaged: $40/month

- Total: $652/month

Fixed Expenses (must pay):

- Phone bill (portion parent doesn’t cover): $30

- Car insurance (their portion): $100

- Gas: $80

- Spotify/Netflix: $15

- Total fixed: $225/month

Variable Expenses (somewhat controllable):

- Eating out with friends: $80

- Entertainment (movies, activities): $60

- Clothing: $50

- Personal care: $30

- Gifts for others: $20

- Total variable: $240/month

Savings Goals:

- Emergency fund (building to $1,000): $50/month

- College expenses: $50/month

- Car repair fund: $30/month

- Total savings: $130/month

Total budgeted: $595/month Remaining: $57/month (buffer for overages or additional savings)

The Budget Creation Process

Guide them through professional-level budgeting:

Step 1: Track Current Spending Before creating a budget, track everything for one month:

- Every purchase, no matter how small

- Every income source

- Every expense

Use app (Mint, YNAB) or spreadsheet.

Step 2: Categorize Group spending into categories:

- Fixed (same every month)

- Variable (changes but somewhat predictable)

- Discretionary (purely optional)

Step 3: Analyze Look for patterns:

- Where does money go?

- Any surprises?

- What feels wasteful?

- What matters most?

Step 4: Create Forward Budget Based on analysis, create next month’s plan:

- Must-have expenses

- Savings goals

- Discretionary allocation

- Emergency buffer

Step 5: Live the Budget Track against budget throughout month.

Step 6: Review and Adjust End of month: What worked? What didn’t? Adjust next month’s budget accordingly.

Advanced Concepts

Introduce sophisticated ideas:

Zero-Based Budgeting: Every dollar has a job. Income minus all allocations = $0.

“You have $652 coming in. Allocate all of it:

- $225 to fixed expenses

- $240 to variable expenses

- $130 to savings

- $57 to additional goals or buffer = $652, exactly what you’re earning”

The 50/30/20 Rule: Adult budgeting guideline:

- 50% to needs

- 30% to wants

- 20% to savings

For teenagers: More like 35% needs / 30% wants / 35% savings (since they have fewer needs and should save more).

Irregular Expense Planning: Some expenses aren’t monthly:

- Car registration: $150/year = $12.50/month

- Birthday gifts: $200/year = $16.67/month

- School supplies: $100/year = $8.33/month

Budget monthly for these annual expenses so money’s available when needed.

The Variable Income Solution: If income fluctuates (commission, tips, gig work):

Method 1: Budget based on minimum expected income. Anything above is bonus.

Method 2: Average last 3-6 months and budget that amount.

Method 3: Build larger buffer for low-income months.

Real-World Preparation

Use their teenage budget to teach adult concepts:

The Life Expense Discussion: “Your budget is $652/month, or $7,824/year. That’s substantial! But notice:

- Parents still pay for housing, utilities, food, health insurance, most of car insurance

- These are expensive: easily $2,000-3,000/month

- When you’re independent, you’ll need to cover everything

- Let’s calculate what salary you’d need…”

Use our Salary Breakdown Calculator to show the full picture.

The Lifestyle Inflation Warning: “When you get a raise, your first instinct will be to increase spending immediately. Resist! Instead:

- Maintain current lifestyle

- Direct raises to savings/investing

- Increase spending only deliberately and slowly

- This is how wealth is built”

The Emergency Fund Priority: “Notice you’re saving $50/month to emergency fund. Why?

- Unexpected expenses always happen

- Without savings, emergencies force debt

- Goal: 3-6 months of expenses saved

- This gives you options and peace of mind”

Show them our Emergency Fund Calculator.

The Investment Introduction: “Once your emergency fund reaches $1,000, consider investing some long-term savings:

- Money sitting in savings loses value to inflation

- Invested money grows significantly over time

- Starting young is incredibly powerful”

We’ll cover this more in Part 6 on investing.

Digital Banking

Teenagers should use real financial tools:

- Checking account for regular transactions

- Savings account for emergency fund and goals

- Budgeting app connected to accounts

- Understanding of online banking

- Awareness of fees and how to avoid them

Practical Budget Systems

Different systems work for different families and ages.

The Cash Envelope System

How it works:

- Determine budget categories and amounts

- Get cash equal to each category’s budget

- Put cash in physical envelopes labeled by category

- Spend from appropriate envelope

- When envelope is empty, spending in that category stops until next budget period

Pros:

- Extremely visual and tangible

- Impossible to overspend

- No tracking needed

- Powerful psychological feedback

Cons:

- Requires handling cash

- Not practical for all purchases (online, etc.)

- Can be lost or stolen

- Inconvenient for teens/adults

Best for: Ages 6-12 learning fundamental budgeting concepts.

The Jar System

Simplified version of envelopes for younger children:

- Clear jars instead of envelopes

- Can see money accumulating

- Makes savings growth visible

- Perfect for 3-10 year olds

The Spreadsheet Method

How it works:

- Create categories in spreadsheet

- Log every transaction

- Running total shows remaining in each category

- Review and adjust regularly

Pros:

- Flexible and customizable

- Can track history

- Good for learning Excel skills

- Free

Cons:

- Requires discipline to log everything

- Not automatic

- Can feel tedious

Best for: Ages 11-14 learning digital tracking and becoming comfortable with spreadsheets.

The App-Based System

How it works:

- Use budgeting app (Mint, YNAB, Goodbudget, PocketGuard)

- Link to bank accounts for automatic tracking

- Set budget limits per category

- App alerts when approaching limits

Pros:

- Automatic transaction import

- Real-time updates

- Notifications and reminders

- Analytical insights

Cons:

- Requires smartphone

- Less tangible than cash

- Some apps have fees

- Privacy concerns (depends on app)

Best for: Ages 14-18 (and adults) managing real income and multiple accounts.

The Hybrid System

Combine approaches:

- Cash envelopes for variable categories (entertainment, eating out)

- Digital tracking for fixed bills

- Savings automatically transferred to separate accounts

Many find this optimal—combines tangible feedback of cash with convenience of digital for appropriate categories.

Common Budgeting Challenges

Challenge #1: “Budgets Feel Restrictive”

Problem: They resist budgeting because it feels limiting.

Solutions:

- Reframe: “Your budget gives you $20 for entertainment. That means you can spend up to $20 guilt-free!”

- Emphasize control: “You decide how to allocate your money, not random impulses”

- Show results: “You’ve been budgeting for 3 months and saved $150! Without a budget, where would it have gone?”

- Make it positive: Budget for fun, not just necessities

Challenge #2: “They Keep Going Over Budget”

Problem: Regularly exceed budget categories.

Solutions:

- Are budgets realistic? Track actual spending first, then budget based on reality

- If using digital, consider cash envelopes for problematic categories (physical limit)

- Identify triggers: What causes overspending? Boredom? Friends? Emotions?

- Build in buffer category for overages

- Review why: Impulse? Necessity? Poor planning?

Challenge #3: “They Don’t Track Consistently”

Problem: Start strong but tracking fades after a week or two.

Solutions:

- Make it easier: Use app with automatic tracking instead of manual

- Reduce frequency: Weekly reviews instead of daily

- Simplify categories: Fewer categories = less tracking

- Make it routine: “Every Sunday after dinner we review budgets”

- Gamify: Tracking for 30 days straight earns a reward

Challenge #4: “Irregular Income Makes Budgeting Hard”

Problem: Income varies significantly month to month.

Solutions:

- Budget based on minimum expected income

- Build larger emergency buffer

- Average income over several months

- Prioritize necessities, then add discretionary based on actual income

- Learn to say “I need to see how much I earn this month first”

Challenge #5: “They Rob Savings to Cover Spending”

Problem: Move money from savings categories to spending when they run out.

Solutions:

- Physical separation: Put savings in bank account, not easily accessible

- Make “borrowing” an event requiring parent discussion

- Natural consequences: If they borrow from bike savings, bike takes longer

- Ask: “Is this purchase worth delaying your goal?”

- Some flexibility is okay occasionally, but pattern needs addressing

Teaching Budget Principles

Beyond mechanics, teach underlying principles:

Principle 1: Income Must Exceed Expenses

Teach: “If you consistently spend more than you earn, eventually you’ll have nothing. The budget ensures spending stays below income.”

Warning: “Many adults violate this with credit cards, creating debt. Budget prevents this.”

Principle 2: Plan Before Spending

Teach: “Budget before money arrives. Decide where it goes before temptation hits.”

Warning: “Without a plan, money disappears and you wonder where it went.”

Principle 3: Every Dollar Has a Job

Teach: “Don’t leave money unassigned. Even ‘miscellaneous’ or ‘buffer’ are assignments.”

Reason: Unassigned money gets spent thoughtlessly.

Principle 4: Budgets Should Reflect Values

Teach: “Your budget shows what you value. If you say family is important but never budget for family activities, what does your budget say you actually value?”

Exercise: Review budget. Does it match stated priorities?

Principle 5: Flexibility Within Structure

Teach: “Budgets aren’t rigid. Adjust when needed. But adjustments should be conscious decisions, not automatic violations.”

Balance: Discipline with adaptability.

Principle 6: Future You Will Thank Present You

Teach: “Budgeting for savings and goals is present-you taking care of future-you.”

Perspective: “Future you will either thank present you for budgeting or resent present you for not budgeting.”

Taking Action Today

Ready to start teaching budgeting? Here’s where to begin:

For Young Children (3-5):

- Set up 2-3 clear jars (Spend, Save, Share)

- Practice dividing money among jars

- Count money in jars together weekly

- Celebrate when Save jar reaches a goal

For Elementary Age (6-9):

- Expand to 4-5 categories

- Create simple tracking chart

- Do weekly budget reviews together

- Let them make small budget decisions

For Pre-Teens (10-12):

- Introduce written budget with 6-8 categories

- Teach budget creation process

- Begin monthly comprehensive reviews

- Introduce our Budget Calculator

For Teenagers (13+):

- Create complete budget covering all income and expenses

- Track spending for one month before budgeting

- Use banking app or budgeting software

- Move toward independent budget management with periodic check-ins

Conclusion

Budgeting is the skill that transforms other financial knowledge into results. You can understand saving, spending, and earning, but without budgeting, these remain abstract concepts rather than coordinated actions.

Children who learn to budget early develop an intuitive sense of financial management that serves them throughout life. They see money as a tool to allocate thoughtfully rather than something that mysteriously appears and disappears. They make conscious trade-offs rather than wondering where their money went.

Start simple with jar systems and basic categories. Build gradually toward sophisticated financial planning. Celebrate successful budgets and learn from unsuccessful ones. Model budgeting in your own life.

The children who learn to budget don’t just have more money—they have more control, less stress, clearer goals, and the confidence that comes from managing their resources effectively. That’s a foundation for financial success and life satisfaction.

Continue Your Journey

Ready to teach your kids about borrowing, interest, and credit? Continue with Part 5: Teaching Kids About Debt to help them understand how debt works and how to use credit responsibly.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age should I start teaching budgeting?

You can introduce basic allocation concepts as early as age 3-4 with simple jar systems (spend/save/share). Formal budgeting with multiple categories works well starting around age 6-8. By ages 10-12, they can handle sophisticated budgets with many categories. Teenagers should be managing nearly complete budgets approaching adult complexity. The key is matching complexity to developmental stage—start simple and build gradually.

Should budgets be rigid or flexible?

Both! The structure should be consistent (regular budget reviews, defined categories, allocation percentages), but content should be flexible (adjust categories, change allocations, adapt to changing circumstances). Teach: “We follow the budget, but we can change the budget when needed through conscious decision.” The worst approach is either ignoring budgets entirely or treating them as unchangeable commandments. Balance discipline with adaptability.

What if my child’s budget doesn’t balance (spending exceeds income)?

This is a valuable teaching moment! Don’t immediately bail them out. Instead, work through the problem together: “You want to spend $60 but only have $40 coming in. What are your options?” They can: (1) Reduce spending in some categories, (2) Extend timeline for goals, (3) Earn additional money, or (4) Eliminate some wants entirely. This teaches real-world budgeting—adults face this constantly. Learning to solve it at age 10 with small amounts prepares them for solving it at 30 with large amounts.

My child tracks spending for a few days then stops. How do I build consistency?

Make tracking as easy as possible: use apps that automatically import transactions instead of manual logging, or use cash envelope system that requires no tracking. Reduce frequency: weekly reviews instead of daily. Make it routine: same time every week without fail. Gamify: 30 days of consistent tracking earns a reward. Start with just one or two categories. Remember: Some tracking is better than no tracking. Build the habit with easy wins before expanding to comprehensive tracking.

Should I let them make budget mistakes or prevent them?

Let them make mistakes when stakes are low! If their budget is poorly constructed and they run out of money mid-month, let them experience that consequence (don’t rescue them). Ask reflective questions: “What happened? Why did you run out? What would you do differently?” They’ll learn more from one experienced consequence than ten prevented ones. However, prevent truly harmful mistakes (like giving away all their money or making dangerous purchases). The goal is learning through experience, not suffering unnecessary harm.

How do I teach budgeting when our family finances are tight?

Financial constraints actually make budgeting more important, not less. You can teach budgeting with any income level—even $5/week allowance can be budgeted across categories. Be honest at an age-appropriate level: “Our family has to budget carefully to make sure we can pay for everything we need.” Model your own budgeting. Use free tools: jars, printable charts, free apps. Focus on the skills and thinking, not the amounts. Children who see parents budget successfully despite constraints often develop excellent financial habits themselves.

What percentage should go to each budget category?

This varies by age and circumstances, but here’s a reasonable guideline: Young kids (6-9): 40% spending, 40% saving, 10% sharing, 10% emergency. Pre-teens (10-12): 30% spending, 40% saving (divided among short/medium/long-term), 10% giving, 10% emergency, 10% other categories. Teens with jobs: Roughly 35% necessities, 30% discretionary, 35% savings. But these are starting points—adjust based on their goals, income, and life circumstances. What matters most is the habit of intentional allocation, not specific percentages.

Should I review their budget with them or let them manage independently?

Age-dependent: Ages 6-9: Review together weekly. Ages 10-12: Review together bi-weekly or monthly with daily management by them. Ages 13-15: Monthly check-ins, mostly independent. Ages 16-18: Quarterly check-ins, fully independent management with you as advisor. Gradually extend independence while remaining available for guidance. The goal is independence by adulthood, achieved through progressive responsibility with appropriate support.